Let's start with a C major scale once again. This time, I'm presenting it both ascending and descending, so you can hear it better.

But that's not the way it works out. There is no note in the C major scale whose frequency is 16/9 that of C. A is too low; B is too high. So the fourth note in the F major scale has to be some different note, a note that's in between A and B. It's like we took a B, and bent its pitch down just enough to make it fit and sound right in an F major scale. We call this note...

Voilà!

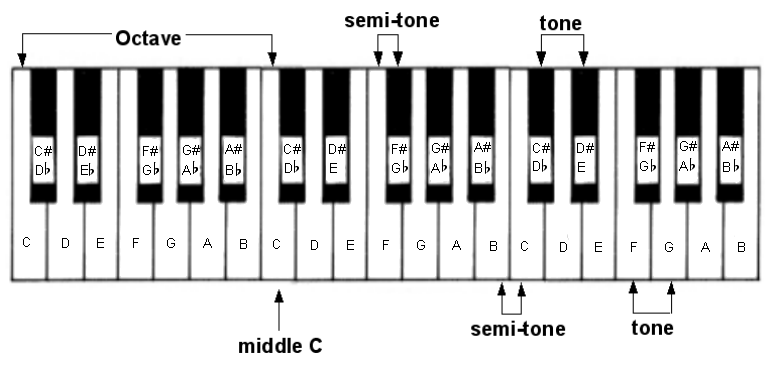

The note in between C and D is C sharp, or D flat.

The note in between D and E is D sharp, or E flat.The note in between F and G is F sharp, or G flat.

The note in between G and A is G sharp, or A flat.

The note in between A and B is A sharp, or B flat.

On the diagram above, you can see an octave labeled. There's also two other terms there that are very useful to know: semitone, and tone. A semitone is the interval between one note and its nearest neighbor, up or down. The notes F and F# differ by a semitone. So do the notes B and C, because they're right next to each other. When you put two semitones together, you get a tone, or a whole tone. C# and D# are a whole tone apart: from C# to D is a semitone, from D to D# is another semitone, and two semitones put together make a whole tone. From F to G is also a whole tone. F to F#, F# to G - each one of those steps is a semitone.

(You'll often hear the words half step and whole step used, instead of semitone and whole tone. They mean exactly the same thing.)

Next time, we'll use semitones and whole tones (or half steps and whole steps) to show how major and minor scales are built.